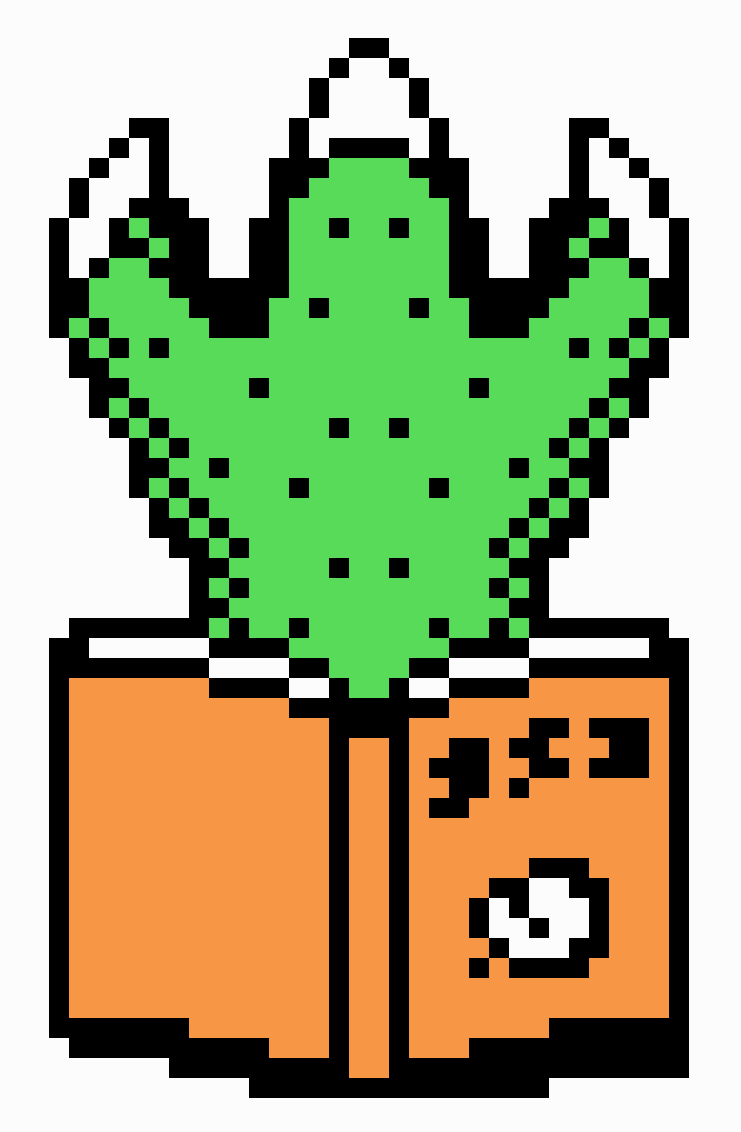

Never having bought a physical copy, I’d only seen the cover art for Neko Case’s 2006 album

Fox Confessor Brings the Flood all squinched and shrunken in my iPhone screen. When I finally saw a high-res version a few days ago, I was pleased to learn that no, that isn’t a misshapen but monolithic bouffant the girl is sporting: It’s just the shadowy landscape behind her. Roll your chair back and make your eyes go blurry if you can’t see how I could have mistaken that shape for a Selma Bouvier-style ’do.

This seemed relevant at the moment — a phrase I find myself saying more and more often

these days — and so I posted it on Facebook. My friend

Bri asked me what the hell that album title was referring to. I had no idea, I realized. I looked. Here’s what I found out.

In 2006, Case

told the Chicago Tribune that the album was her way of examining fairy tales:

I’ve always been fascinated by fairy tales, but we really don’t have fairy tales anymore. Movies have taken their place, and modern fiction seems to be in this rut of the coming-of-age story, which is getting really boring. I’m trying to find things on the outer limits of experience. I really love the Eastern European fairy tales because they're not only dark but they're also funny and not overly moral.

In the same article,

Tribune music critic Greg Kot makes two more points about the “country noir” album’s allegorical nature:

Case’s heavy use of symbolism is also a means of avoiding more confessional and autobiographical songs, of which she has also tired. There’s plenty of Case’s story in these songs, it’s just more artfully veiled.

and

In the world staked out by Fox Confessor, life is divided into predators and prey, and Case’s songs are a menagerie of symbolic characters drawn from the eat-or-be-eaten wild: the naive sparrow, the devouring lion, the vampire who has a “tender place in my heart for strangers.”

All that was enough to make me think that Neko probably presented the album — the title, the lyrics and even the art — with at least a general symbolic game plan in mind, but like Kot says, the meaning is not necessarily obvious, and I had no idea what story she may be trying to tell with the album title, an apparent reference to an old world fairy tale about a fox and a wolf. Here’s

the full text of one version, and for the TL/DR crowd, here’s my Cliffs Notes version: A thirsty fox wanders into a well to get a drink, but when he steps onto the water bucket, he sinks to the bottom. Down there, he’s doubly screwed because there’s no drinkable water, and he can’t get back up, but then a wolf comes along, and the fox tells the wolf that the bottom of the well is, in fact, paradise, but he can only enter if he confesses all his sins to the fox. The wolf does, and then the fox tells him to step into the other bucket. As the wolf moves down into the well, the fox’s bucket is lifted out. The fox runs away, and eventually when some friars go to get water, they find and kill the wolf. The end.

Like Case said, the story doesn’t beat you over the head with its moral, but the full text includes an intro that says it was a satire of religious hypocrisy, with the fox confessor — remember, a confessor in this context is probably the person hearing the confession, even though that word

can also mean the person listing off their sins — offering the wolf promises of salvation but ultimately leaving him worse of than he was in the first place. (Oddly and perhaps notably, the text includes an untranslatable phrase,

the widow’s curse, which case seems to be subverting in another

Fox Confessor track,

“A Widow’s Toast,” but again I’m unsure to what end. For what it’s worth, that song also has explicitly religious, explicitly Catholic themes.) This version of the “fox and wolf” story also lacks a flood — in fact, there’s the opposite of a great deal of water waiting at the bottom of the well — but it’s apparently just one variation on a theme.

I also found Scott Reid’s

review of Fox Confessor for Coke Machine Glow, in which he describes a Ukrainian version of the fable that ends with the wolf entering the ocean because he foolishly believes the fox’s claims that he can control the tides. (It does not end well for the wolf.) From this review:

[T]o grossly oversimplify some really harsh but “darkly funny” (according to Neko) animal mythology, Fox Confessor Brings the Flood = the person-wild animal-higher power that you put your faith in fools you, so not only are your sins not absolved, there’s this big (pre-existent, not actually of confessor’s control) shit-flood that’s gonna wreck you and leave you either abandoned and begging for sweet reprieve or corpsed up on your predator’s doorstep like the old guy who married Anna Nicole Smith.

The review makes some interesting connections, but I in particular enjoy Reid’s analysis of the album’s title track, which actually features a fox confessor as a character.

It’s also example of how beautiful and dark and intriguingly abstract Neko Case can be, and why I’m still fiddling with this album seven years later. Writes Reid:

Here, [the narrator] drives by “beautiful” flooded fields in the first verse and floods her own sleeves (finally realizing she has nothing to “hold [her] faith in,” she breaks down) in the last. Both scenes bookend a confrontation with the fox confessor, who she follows, guilt-ridden, in “retreat.” But in retreat from what? The flooded fields? Well, no — in those she finds beauty, as any good gothic protagonist would. It’s the flooded sleeves, the emotional manifestation of her “orphan blues,” that leaves her so vulnerable and defeated. So, when the fox confessor tells her that it’s not her fault and understands her frustration (“It’s not for you to know / but for you to weep and wonder / when the death of your civilization precedes you”), of course she’s going to follow him, accepting that wherever it leads her will be a step up from what she’s going through. She ultimately gives in because she’s burdened with a monumental sense of loss: of faith, self-respect, options, love, power, hope, sanity, all that good shit. She’s inundated by an overwhelming lack of control and direction, left a pessimistic emotional wreck that’d rather accept a foolishly romanticized concept of death than deal with her own demons.

And finally, Reid even ties these themes in to

Julie Morstad’s album cover illustration, which again intrigues me but doesn’t seem to fit in with any of the symbolism laid down in the lyrics or the folklore, aside from there being a female protagonist, foxes and that prevalent dark, mysterious beauty.

And here is some art from inside the CD jacket, where it’s easier to see that the girl has cloven feet:

Reid makes as good an analysis as any:

The cover depicts a surreal combination of fable and subject: a black-haired girl with the cloven feet cradles severed heads. It gives the impression that she has some sort of ownership of death (the heads are hers, after all), an impossibility that just sets a defeating cycle in motion: that false ownership both temporarily distracts (she has to run out of heads sometime, then the foxes get her) and lures the fox, trapping the girl in frustration and guilt.

This is what I found, anyway. Of course, I’d be happy to hear how anyone else can put the pieces together. Meanwhile, listen to “Hold on, Hold on” again, and see what it shakes loose.