This was a big week for fans of samesies, but while many Californians took to the streets to celebrate the Supreme Court, I observed this momentous occasion by working at home and then falling asleep watching Comedy Central. It’s for this reason that I’m presenting a bit of gay history today. It may not affect as many people as does California catching up to that glittering bastion of liberality we call Iowa, but it’s a pretty good story nonetheless. Also, I just learned it yesterday, and it’s one of the best things I’ve learned in a long time.

Last April, pro basketball player Jason Collins announced he was gay, prompting many media outlets to decree that he was the first to come out while being a member of a major American sports team. Some, however, noted that this wasn’t the case: In particular, the

San Francisco Chronicle noted that

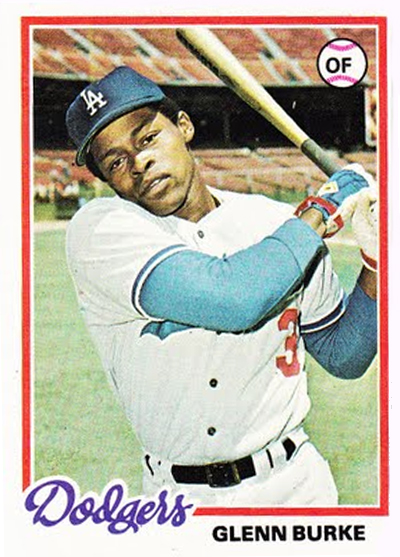

Glenn Burke, who joined the Dodgers as an outfielder in 1976, was out to his teammates.

Burke’s sexuality wasn’t exactly known to the public, but it wasn’t for a lack of effort on Burke’s part. From

The Atlantic:

Burke made no secret of his sexual orientation to the Dodgers front office, his teammates, or friends in either league. He also talked freely with sportswriters, though all of them ended up shaking their heads and telling him they couldn't writethat in their papers. Burke was so open about his sexuality that the Dodgers tried to talk him into participating in a sham marriage. (He wrote in his autobiography that the team offered him $75,000 to go along with the ruse.) He refused. In a bit of irony that would seem farcical if it wasn't so tragic, one of the Dodgers who tried to talk Burke into getting "married," was his manager, Tommy Lasorda, whose son Tom Jr. died from AIDS complications in 1991. To this day, Lasorda Sr. refuses to acknowledge his son's homosexuality.

The Atlantic notes that Burke came out in a bigger way in a 1982 interview. He died from AIDS-related causes in 1995. This story itself seems worth telling, or at least worth telling if you’re anyone who cares about the various Jackie Robinsons of the world, but there’s actually an even more surprising footnote to Burke’s short baseball career: He may have invented the high five.

I know, I know. It’s weird to think of a word in which people didn’t slap palms as congratulations for a feat of athletic awesomeness, a perfectly barbed put-down, a righteous belch or “yeah, I hit that,” but we didn’t always have this gesture. In the way that it can be tough to determine exactly when a slang phrase enters the lexicon, we also can’t be sure exactly when high-fiving went mainstream, but Glenn Burke and Dusty Baker seem to get credit for giving the first on-the-record high five on Oct. 2, 1977, just after Burke hit his thirtieth home run.

This ESPN.com article, notably written just a few days before Collins came out, does a fantastic job telling the story:

It was a wild, triumphant moment and a good omen as the Dodgers headed to the playoffs. Burke, waiting on deck, thrust his hand enthusiastically over his head to greet his friend at the plate. Baker, not knowing what to do, smacked it. “His hand was up in the air, and he was arching way back,” says Baker, now 62 and managing the Reds. “So I reached up and hit his hand. It seemed like the thing to do.”

The article, which goes on to describe the ambiguous relationship Burke shared with Tommy Lasorda’s son, says that the high five went “ricocheting around the world” from there, in spite of the fact that the game wasn’t televised. And there you have it. Yes, it does seem strange that the high five was born only a few years before I was, and yes, it’s entirely possible that someone else in the history of the world slapped someone else’s palms in a victorious fashion. But if they did, we don’t know about it. We do know about Glenn Burke, who along with Dusty Baker invented something that would live on, even when Burke himself or mainstream awareness of his athletic career or his status as the Jackie Robinson of gay baseball (“gaysball”) did not.

Does this mean that high fives in the early seasons of

That ’70s Show were anachronistic? Yes, I suppose so. Does this not tie in nicely with

what I posted on Wednesday? Yes, it really does. And does this also mean that any and all high fives are tacit endorsements of the gay agenda? Well, obviously.

Now That’s Interesting!, previously: