Call this a spiritual sequel to my post about Ambrose Burnside, the man whose celebrated face wool gave the English language the word sideburns. If you’ll recall, before I knew the etymology, I’d always thought how remarkable it was that a man named Burnside had such magnificent sideburns. It would have been as if Pamela Anderson had born Pamela Bagsfun. Of course, I learned the error in my thinking, but there’s still the strange occasion on which someone’s name ends up being just bizarrely perfect for their station in life.

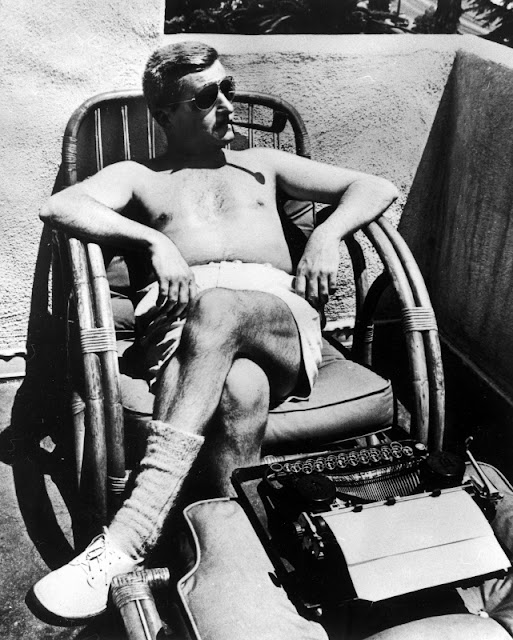

So I like William Faulkner. And that’s not saying that I don’t fear the bastard to some degree, both because anyone who could drink like he could demands that you fear him, and because his stories cause reverberations in a deep part of my brain near where my surreal subconscious lives, and strange things tend to come loose when I spend too much time in a Faulknerian place. In college, I read more of Faulkner than I did of any other single author, and while he has played a less significant role since I graduated, I stumbled upon a little fact about him while writing up a piece on To Have and Have Not, the 1944 Humphrey Bogart-starring adaptation of the Ernest Hemingway novel. Faulkner, improbably, collaborated on the screenplay, and being reminded of this strange Californian dogleg to his career got me reading.

It turns out that during his time in Hollywood, William Faulkner took up with a number of women, but perhaps foremost among them was the script girl to Howard Hawks, who directed To Have and Have Not. This woman was Meta Carpenter, and while there’s much to be said about her life — she worked on The Maltese Falcon, Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, Prizzi’s Honor, and The Graduate, according to IMDb and her New York Times obituary, and The Longest Chapter has posted a letter from Ms. Carpenter that shines some light on who she was — I’m just going to focus on her name.

Maybe Meta Carpenter isn’t the most Faulknerian name ever, but let’s say that William Faulkner himself turned in a draft to an editor, and the story featured a writer whose works call back and forth to each other, with characters’ fictional lives weaving in and out of the stories to the point where the author has, chapter by chapter, slat by stat, constructed a self-referencing, self-contained universe. And let’s say that one day that author met a woman whose job was monitoring the scripts upon which movies are built — the verbal scaffolding, if one will. And let’s say that they had a passionate love affair, with dangling clauses dropping into open signifiers. Well, if that happened, even if the author were as esteemed as William Faulkner, and he chose to name the love interest Meta Carpenter, then the editor might very well have called William Faulkner up and explained that perhaps the name was just a little too on-the-nose, and that the story might benefit if he re-named Meta Carpenter something that didn’t seem to cut quite so straight to the heart of what she was, what he was, and really, what any great writer is.

Of course, Meta Carpenter’s parents named her without any knowledge of the kind of woman she’d be and the role she’d play in coaxing life from words and word-makers.

The fact that Meta Carpenter eventually married and became Meta Wilde? Well, that’s another post, I think.

Names are not insignificant, even in real life:

No comments:

Post a Comment